A satellite photo of the Korean peninsula at night shows South Korea ablaze with lights and then, as if someone drew a line at the 38th parallel, North Korea ink black except for the tiny dot of Pyongyang. North Korea is a country where public displays of affection are prohibited, international aid workers aren’t allowed to study Korean, the internet doesn’t exist, doctors operate in hospitals without electricity, heat, water, or antibiotics, schools have no books or paper, postal workers burn the mail for heat, attendance at public executions is compulsory, history is reinvented wholesale, religion is forbidden, people step over dead bodies in the street, and, in the late 1990s, upwards of two million people died in a famine — thanks to the Great Leader Kim Il-sung (1912–1994) and his son Kim Jong-il (1941–2011). Sudan, Congo and Laos all have higher per capita incomes than North Korea.

A satellite photo of the Korean peninsula at night shows South Korea ablaze with lights and then, as if someone drew a line at the 38th parallel, North Korea ink black except for the tiny dot of Pyongyang. North Korea is a country where public displays of affection are prohibited, international aid workers aren’t allowed to study Korean, the internet doesn’t exist, doctors operate in hospitals without electricity, heat, water, or antibiotics, schools have no books or paper, postal workers burn the mail for heat, attendance at public executions is compulsory, history is reinvented wholesale, religion is forbidden, people step over dead bodies in the street, and, in the late 1990s, upwards of two million people died in a famine — thanks to the Great Leader Kim Il-sung (1912–1994) and his son Kim Jong-il (1941–2011). Sudan, Congo and Laos all have higher per capita incomes than North Korea.

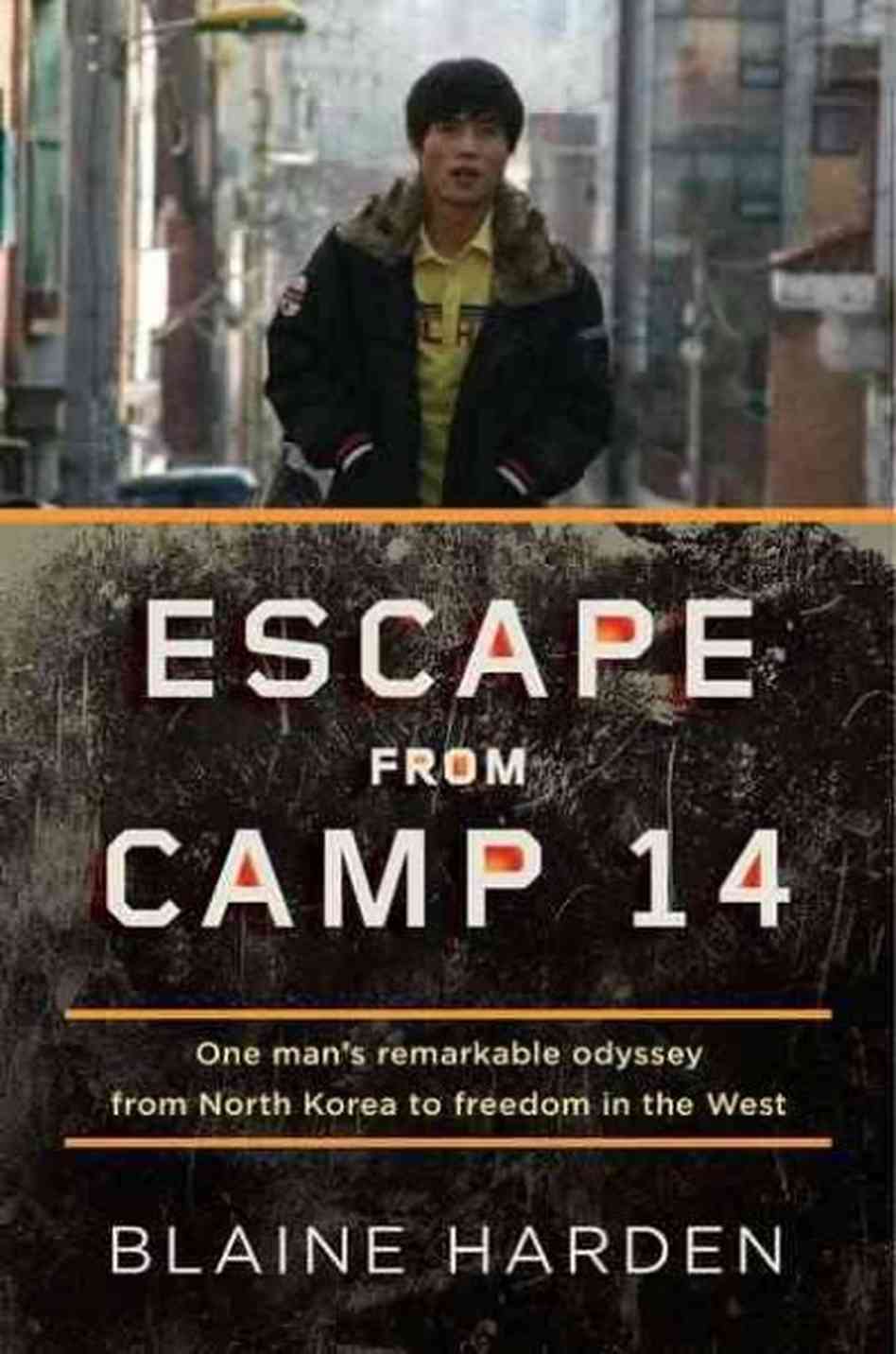

As many as 200,000 citizens also languish in North Korean labor camps. Many thousands have perished in them. You can see exactly where these camps are by using Google Earth. Camps 15 and 18 are for “re-education” of prisoners. Camp 14 is what’s called a “complete control district” for “irredeemables” who are worked to death. There are about 15,000 prisoners in Camp 14. Blaine Harden, a correspondent for the Washington Post, tells the remarkable story of one of them, Shin In Geun. It’s remarkable because Shin was born in Camp 14, and as far as we know he’s the only person born in a labor camp to escape. According to Harden, “just two people other than Shin are known to have escaped from any political prison camp in North Korea and made it to the West.”

Shin documents the worst sorts of human atrocities you might imagine, including six months in an underground dungeon, and being roasted over a fire. Experts who’ve vetted him believe his story. A year after he escaped he began a diary, which eventually resulted in a memoir that was published in 2007 in South Korea (and widely ignored). Harden’s book has enjoyed a different fate; it’s already been translated into 23 languages and made numerous best seller lists. In addition to his many interviews with Shin, he incorporates the insights of human rights activists, other defectors, refugees, and intelligence experts. When Shin escaped Camp 14 on January 2, 2005, he was twenty-three. He knew nothing about the outside world. He had no idea where to go or what to do. It’s not been easy, he says: “I’m evolving from being an animal. But it is going very, very slowly. I escaped physically; I haven’t escaped psychologically.”

reviewed by Journey with Jesus webzine, www.journeywithjesus.net, with founder Dan Clendenin’s permission.