English Reformation to the 21st century

In the time just before the English Reformation, there were many vestments in use: cassock (fur lined for cold churches,), amice, cincture, surplice, tippet, alb (originally an undergarment), fiddleback chasuble, stole, cope, oracle (the short cape popes wear), miter, dalmatic of the deacon, and the tunicle of the subdeacon.

Henry VIII so wanted a male heir that he took wife after wife, annulling most and beheading one. His break with the Roman church in 1534 set up a question of whether to keep the ‘old’ vestments, or alter some shapes, or ban their use. In the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer mandated only these vestments: a blousoned cassock, amice, surplice, alb (some being a full seven yards at the hem), chasuble with matching stole, maniple, tippet, almuce (a fur-lined hood, not to be confused with amice), cope, and dalmatic. Some of these were discontinued, but Cranmer’s preference for simplicity held with the surplice over a cassock and stole or tippet as the basic liturgical garments, even well into the 20th century.

The reign of Elizabeth I saw a return to the pre-Henry VIII climate as she loved the vested clergy, although the chasuble was discarded as being too Catholic (besides which the large fashionable wigs made chasubles impractical). The continued jockeying back and forth between the Church of England and the Catholic church with the ascension of various kings and queens made a quandary for the use of vestments, but fashion and politics often dictated what was used. Put into this mix the rise of the nonconformists (think Puritans/Presbyterians). Clergy began to use everyday dress: suit, vest, knee breeches, shirt with neck cloth and cravat (which warp into the clergy collar and bands by 1650s), and wigs.

The chasuble returned in the 1770s, typically a fiddleback shape, which was often made from donated party dresses of the aristocracy

However, the chasuble returned in the 1770s, typically a fiddleback shape, which was often made from donated party dresses of the aristocracy. You can tell an 18th century chasuble instantly because it has no religious symbols, rather flowers, leaves, and curly stems. The miter came back but was carried in hand and soon after disappeared until the late 1800s. However, the cassock (Anglican is double-breasted), surplice (Anglican has pointed sleeves), and stole continued to be very popular as basic garments for the liturgy, with the cassock with a belt or band cincture for everyday dress. Even seminary students and deacons were to wear cassocks/surplice at all times. After graduation, the academic hood was allowed over these.

With the revival of the Gothic style in the 1800s, Anglican/

Episcopal vestments were made of high

fashion fabric and elaborately decorated.

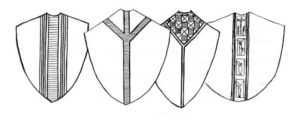

With the revival of the Gothic style by the Oxford Movement in the 1800s, Anglican/Episcopal vestments were made of high fashion fabric and elaborately decorated. The chasuble lost its fiddleback shape, evolving into a straight-edged garment in both front and back with a stole worn underneath. With this return to the many Baroque/Rococo styles, everything was fair game, but the clergy collar was still not used. Not all followed the Oxford Movement trend as the rubrics of the English BCP still mandated cassock and surplice for the liturgy. Innovation was limited and low-key. The 19th century continued with some variation, including the spade stole worn under the chasuble, clearly 1920s. Color based on the liturgical calendar was common. But most Episcopal clergy kept the cassock and surplice until the 1950s.

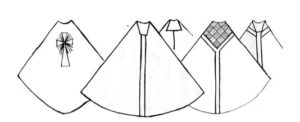

With the renewal of the Catholic church in Vatican II, all denominational doors were opened to creativity. New hymnals, new liturgies for a variety of situations, new textile designs were created for vestments, banners, and paraments. The Episcopal church joined in. The Eucharistic vestments are alb/stole/chasuble; the latter is now a full circle garment because of the drape of new fabrics. Stoles are worn outside the chasuble by personal preference. The collar returned in the 1950s.

About the author: Marylyn Doyle, an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, taught textile art for 23 years at Union Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. She has shared her vast knowledge of the history of vestments, as well as teaching embroidery and needlework in seminars across the country with all denominations.